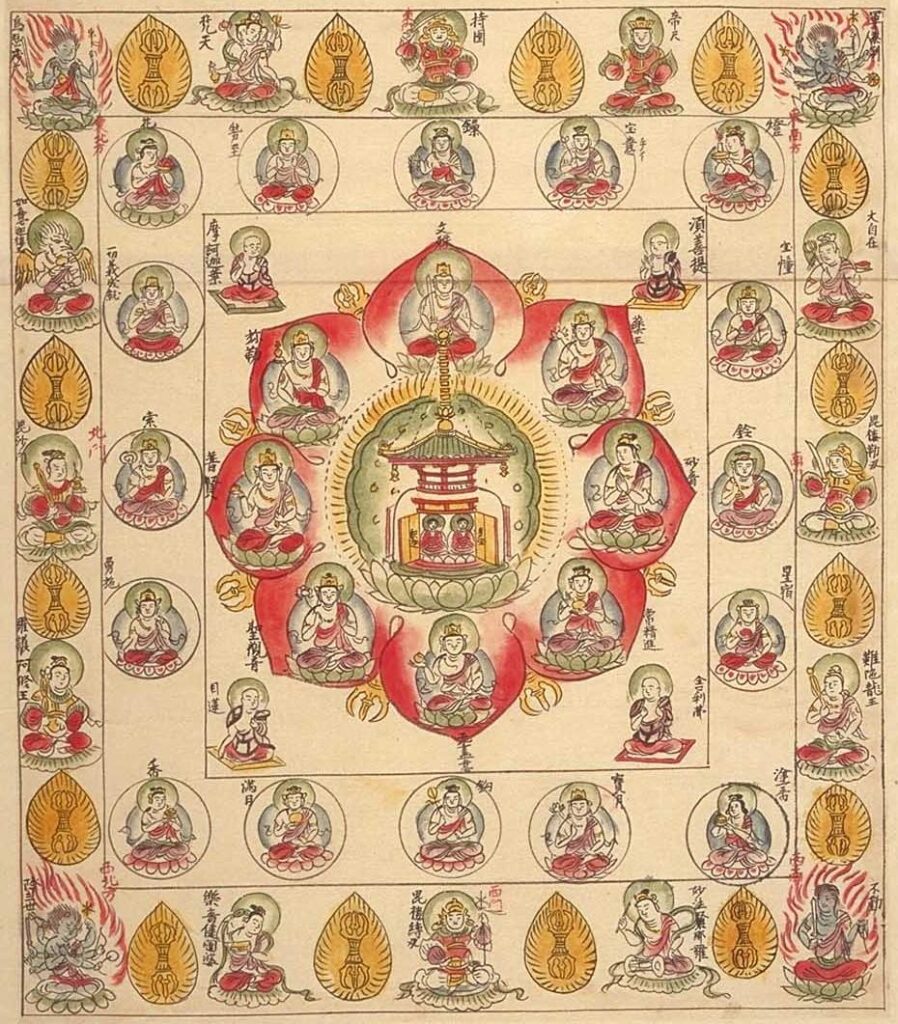

Wikimedia Commons File: Hokke mandala, 12th century

Even though the realm of enlightenment cannot be expressed in everyday language, Esoteric Buddhism has another way to enable this: the mandala.

Introduction

In the course of its long history, Buddhism has undergone many changes as it expanded and developed. Of these, one of the most significant was the emergence of Mahayana Buddhism around the first century BCE, followed by the rise of esoteric teachings and practices some five or six centuries later. While Esoteric Buddhism is thought of as an extension of later period Mahayana, it is undeniable that there are considerable differences between the two in both doctrine and practice. By distinguishing between them, we can come to a better understanding of the distinctive features of each.

One such feature is that they have completely different objectives. Of course, they both share the same foundation—the tenets of compassion and dependent origination—but they differ greatly in their perspective on Buddhism. If the focus of attention is not the same, it is only natural that major differences will emerge. What is of prime importance in Buddhism is the fact that Śākyamuni achieved enlightenment, and then did not keep it to himself but transmitted it to the world at large. Whereas Mahayana focused on spreading his teachings widely throughout society, Esoteric Buddhism rather emphasized the attainment of enlightenment itself. For Mahayana, then, taking very seriously the Buddha’s altruistic practice over forty-five years, the first and foremost duty of Buddhism is the spiritual liberation of all living beings. In other words, Mahayana does not place importance on religious practice aiming at one’s own attainment of buddhahood, but on the core value of action to liberate living beings within society. In concrete terms, this means that Mahayana makes the Way of the Bodhisattva, upon which both the layperson and the ordained walk together, the basis of its teaching, as well as its activities, are the dynamic force in spreading the teachings of Buddhism throughout the world.

The Mandala: Representing Enlightenment

While Mahayana focuses on our lives, as we have seen, Esoteric Buddhism has as its objective the sacred realm of enlightenment. Kūkai, the ninth century Japanese priest who formulated esoteric doctrine, clearly stated that the core of Esoteric Buddhism is the religious practice of the ordained practitioner. He said that the ultimate aim of Buddhism is “to attain enlightenment in this very body” (J. sokushin jōbutsu). By contrast, Mahayana holds that “the realm of enlightenment is profound, far beyond human conjecture,” and that it cannot be experienced by anyone other than a buddha. It is a state described by the expression, “The path of words has been cut off,” meaning that we cannot speak of it in our everyday speech and writing, and summarized by the compound “cessation of mental activity,” saying that it is a state far exceeding human intellection. It is not surprising, therefore, that Mahayana does not prioritise practice aimed at enlightenment but rather emphasizes that which leads living beings to liberation and salvation.

Even though the realm of enlightenment cannot be expressed in everyday language, Esoteric Buddhism has another way to enable this: the mandala. It is not written in letters and characters like the scriptures, but rather expresses comprehensively the workings of enlightenment and wisdom using not words but only “form and color.” Kūkai, in his search for the esoteric teachings, went to China with the purpose of obtaining mandalas that portrayed the realm of enlightenment in pictorial form. He eventually arrived at the Qinglong Temple in Chang’an where he was accepted as a student by Huiguo, and in a few months received the final esoteric initiation, enabling him to take the mandalas he so dearly sought back to Japan. According to the inventory of items he brought with him from China, these mandalas included the Great Compassion Womb Realm Mandala, the Great Compassion Womb Realm Dharma Mandala, the Great Compassion Womb Realm Samaya Mandala, the Diamond Realm Mandala in Nine Assemblies, and the Diamond Realm Mandala with Eighty-One Divinities.

Huiguo, who gave these mandalas to Kūkai, said, explaining the primacy of the mandala in which was depicted the essence of the esoteric teachings, “The secret treasury of Shingon is hidden from the commentaries; it can only be transmitted through diagrams and paintings.” Large numbers of buddhas and bodhisattvas, among others, are depicted in the mandalas, but the latter are far more than just pictures. The pictures in a mandala represent the enlightenment of the secret treasury of Shingon, and the working of wisdom. At the same time, it seeks to fuse the two. If we can contemplate the mandala correctly, we too can enter the realm of enlightenment.

The Four Types of Mandalas

Mandalas depicting the inner reality of enlightenment are not intended to be explained or understood through words, but rather to be experienced by the practitioner becoming one with the images drawn within them. The realm of enlightenment is not to be understood intellectually; rather it is something that is embodied by the Shingon practitioner as the culmination of his or her training. Esoteric Buddhism teaches the practice of the “three mysteries” as the training to embody enlightenment. The “three mysteries” refers to that domain in which the activities of the body, speech, and mind of the practitioner become one with those of the Buddha. This, in other words, is the form of one who has attained enlightenment. The practice of the “three mysteries” is the religious training of Esoteric Buddhism. The Shingon practitioner aspiring to enlightenment makes mudras with his hands, recites mantras with his mouth, and maintains a mind of perfect quietude. And it is the mandala that expresses that realm of unity between the practitioner and the Buddha.

To put it simply, the mandala portrays the actuality of the “three mysteries” practice as a picture. Kūkai spoke of this actuality in terms of the “four mandalas.” In his Sokushin jōbutsugi (On attaining enlightenment in this very existence), he quoted from the Mahāvairocana Sūtra, describing the four forms of the mandala as follows:

The Mahāvairocana Sūtra says that “there are three esoteric forms of expression [i.e., of enlightenment] for all the Tathāgatas. They are letters, mudras and images. “Letters” refers to the Dharma Mandala, “mudras” or symbols refers to the Samaya Mandala, and “images,” or the marks of the physical form of the Buddha, refers to the Great Mandala. Implicit in each of these three mandalas are the proper deportment and activities that are called the Karma Mandala.

Great Mandala

The Great Mandala expresses each of the buddhas and bodhisattvas through their marks of physical excellence, and they are depicted wearing garments of various colors. They are the personification of the ways in which the wisdom of Mahāvairocana operates, and they express the working of that wisdom in the practice of the fivefold meditation and in attaining unity with the figure being meditated upon. The “fivefold meditation for realizing buddhahood” is a practice unique to Esoteric Buddhism. It consists of five meditations to achieve the body of a buddha, with the purpose of concentrating the mind on one point and merging with enlightenment. The first meditation is to visualize the mind to be like the full moon, and the second is the perfection of the previous meditation. The third is to see the mind as a diamond, while the fourth is attaining the adamantine (samaya) body. The fifth is to become one with the Buddha. A good example of a mandala that expresses this is the central “Perfected Body Assembly” of the Diamond Realm Mandala.

Samaya Mandala

The Samaya Mandala is known as the “secret” mandala. Samaya is a Sanskrit word whose meaning in Esoteric Buddhism is explained as the working of the Buddha-mind that has empathy for living beings. It is defined as “original vow,” the vow of a buddha or bodhisattva to liberate living beings. A way to convey this original vow is through symbolic forms such as the various implements or accessories associated with the buddhas and bodhisattvas that represent those vows. They include swords, wheels, vajras, and lotuses. Mudras performed by joining the hands together are also included here. The Samaya Mandala thus depicts objects representing the deities. An example is the “Samaya Assembly” in the middle of the bottom row of the Diamond Realm Mandala.

Dharma Mandala

Because the Dharma Mandala is made up of Sanskrit letters, it is also known as the “mandala of words” or the “mandala of the mouth-mystery.” And since it uses Sanskrit letters to represent the deities, it is also known as a “seed-syllable mandala.” Mandalas have Mahāvairocana as their foundation, and depict the buddhas and bodhisattvas who represent his workings, but in a “seed-syllable mandala,” Sanskrit letters alone are used. The word “seed” (Skt bīja) is used here to indicate that all is concentrated within the mandala, like flowers and trees growing from a seed. Sanskrit letters are chosen because they are the sacred characters used to write the sutras.

Karma Mandala

The Sanskrit word karma means “action” or “behavior.” The Karma Mandala represents the dynamic state of enlightenment—that is, the noble activities of buddhas and bodhisattvas. This is expressed physically using statues of sacred beings; the three-dimensional mandala of twenty-one sculptures at Tōji is an example of a Karma Mandala. However, since this mandala too expresses the figures of buddhas and bodhisattvas, it can also be termed a Great Mandala. It is difficult to give form to the workings of enlightenment, which permeate all existence, and so the Karma Mandala is implicit in the other three.

As we see from the above, the four mandalas depict the experience of the three mysteries as a way of expressing enlightenment. Works about the doctrine of Esoteric Buddhism speak of the Dual Mandala—that is, the Mandalas of the Diamond and Womb Realms, where this doctrine is arranged systematically. Given our limited space here, I hope we will have another opportunity to discuss this more fully.

Michihiko Komine is elder of Kanzo’in in Tokyo, a temple belonging to the Chisan branch of the Shingon sect of Japanese Buddhism. His special fields are early Mahāyāna Buddhism and the Shingon Buddhist doctrine. He is the author of numerous books on esoteric Buddhist paintings.