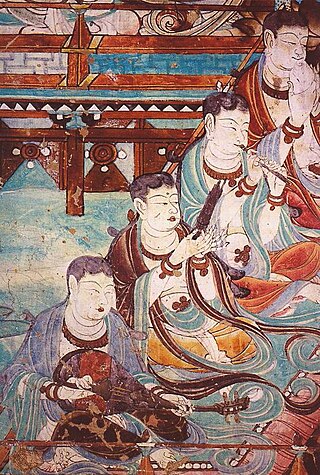

A detail of Musicians in Paradise. Yulin Grottoes, cave 25, in Guazhou County, Gansu Province, China. Sixth century. The musical instruments shown from the left pipa (Jpn., biwa), sheng (a Chinese mouth-blown polyphonic free reed), flute, and conchshell.

Wikimedia Commons File: Traditional Chinese instrument players – Yulin Cave 25.jpg

Music is a skillful means to please laypeople and patrons of the Sangha, or an offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas.

In this essay, we will trace the doctrinal possibilities of music practice as a form of Buddhist practice, from early Buddhist scriptures and Vinaya codes to the long Japanese tradition of performing Gagaku ceremonial music and Bugaku dance at Buddhist rituals.

Buddhist Ambivalence toward Music

Many early Buddhist sources present negative views of music, to the point of prohibiting it. In the Zōitsu Agonkyō (T 2, 1.756c) the Buddha lists the abstinences that lay followers must adopt on fasting days—those include “making music and smearing one’s body with perfumes.” The same sutra also prohibits monks and nuns from discussing music, singing, and dance, because these subjects, along with drinking alcohol and performing comedy, are not appropriate for them (T 2, 1.781bc). Some Vinaya codes also prohibit monks, nuns, and laypeople not only from performing music and dance themselves but also from watching or listening. These texts are primarily addressed to the early communities of Buddhist renunciants who were endeavoring to separate themselves from the lifestyle of ordinary world: they forbid music because it relates to sensual pleasure and to inappropriate deportment.

At the same time, early scriptures also show a positive attitude toward music, singing, and dancing, as long as they are performed in praise of, or as offerings to, the Buddha. They likely acknowledged that music, songs, and dance were important for religious purposes and in communal events in communities where Buddhism was spreading. Melodious sutra chanting is attested since the earliest period in the development of Buddhism, when chanting the scriptures with a beautiful singing voice was praised. For instance, the Zōitsu Agonkyō extols “a clear and penetrating voice that reaches Brahma’s heaven” (T 2, 1.558a23–24), as long as it is to praise the Buddha and his teachings. The Mahāsaṇghika Vinaya (Jpn., Makasōgi ritsu) allows the members of the Sangha to attend music performances organized by lay patrons to commemorate the birth of the Buddha, his enlightenment, or his first sermon (p. 494a). The Buddhacārita (T 192, 4.54a) mentions music performed to celebrate the building of stupas to enshrine the relics of Śākyamuni after his cremation. An even more explicit praise of music offerings is presented in Hōen shurin, when the Buddha attended a music performance in the city of Śravastī: “All these people played music as an offering to the Buddha and the Sangha; because of the merit of that, they will not fall into an evil destination but receive the highest pleasure possible for gods and humans for a hundred kalpas, after which they will become pratyekabuddhas” (T 53, n. 2122: 576c).

In general, Mahayana scriptures tend to show a more positive attitude toward music. The Lotus Sutra says that in a distant past, the Bodhisattva Myōon played music of all kinds for thousands of years to a buddha, and because of that he was reborn in a Buddha-land (T 9, n. 262: 56). The Konkōmyō saishōō kyō describes the voice of Benzaiten as endowed with the power to lead beings to salvation (T 16, n. 665). In Japan, Myōonten and Benzaiten came to be considered the same being, who presided upon a number of rituals involving the transmission of the musical arts.

A distinct thread in Buddhist ideas about music concerns the presence of music in the heavenly realms and the pure lands. A visualization in the Kanbutsu sanmaikai kyō presents “countless songs with musical accompaniment sing the infinite virtues of the Tathāgata” played by Brahma, Indra and a large retinue of heavenly beings (T 643, 15.677b26–c2). The Muryōju kyō (T 360, 12.266a) describes Amida’s Pure Land, with the unsurpassable beauty of the sound produced by the trees made of the seven precious stones, and the myriad kinds of spontaneously produced music in which each sound is the sound of Dharma (hōon); moreover, heavenly beings come to play music for the Buddha and the bodhisattvas. Heavenly music is not a mere adornment of the Pure Land, but a veritable manifestation of the Buddha Amida endowed with the power to lead beings to salvation.

Later on, Esoteric Buddhist (mikkyō) scriptures continue to present music as an offering to buddhas and bodhisattvas; a novelty they introduce is the fact that a musical instrument, the biwa, is described as the sanmayagyō (the symbolic, substitute body) of Benzaiten, thus opening up the possibility for the sacralization of music instruments.

We should point out, however, that most scriptures draw a distinction between human music and heavenly music; the music Śākyamuni was exposed to before leaving his father’s palace was human music, but after his awakening, he only listened to heavenly music. This leaves some doubts on whether human music can have a direct role in Buddhist practice.

Salvific Music

In all these sources music is a skillful means to please laypeople and patrons of the Sangha, or an offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas, or part of the pure lands—in other words, music is never considered a value in and of itself. There are, however, a few exceptions in the Buddhist canon that address music as deeply related to the very core of the Buddhist teachings and practices. These scriptures are not very well known today, as they are not part of the canon of any Buddhist denominations, but they had a significant impact in premodern Japan because they gesture toward the possibility of musical activity in itself as a form of Buddhist practice.

The first of these scriptures is entitled Sutra of the Questions by Indra (Shakudaikan’in mongyō, T 1, n. 1: 62c–66a). In it, the Buddha praises the gandharva Pañcasikha, a virtuoso musician, for the “pure sound” of his beryl koto (the Sanskrit original has vīnā, a string instrument):

The sound of your koto and your own voice . . . move the human mind. The music you play on your koto has many meanings: it talks about desire and attachment, Buddhist practice, the śramanera, and nirvana. (T 1, 1.63a18–20)

Here, Pañcasikha’s music is most definitely not a hindrance for renunciants (as in the monastic regulations), nor a mere offering. Instead, it conveys the fundamental teachings of Buddhism (i.e., the nature of desire and attachment, and how to go beyond them), as well as the principles of correct practice, and as such has the power to lead a Buddhist practitioner (śramanera) to nirvana.

In another early source, the Buddha takes the shape of a gandharva after being challenged by gandharva king Zen’ai on who among them is the best virtuoso player of the koto (i.e., the vīnā). (Gandharvas, and more rarely kiṃnaras, metahuman angelic beings, were considered music virtuosi.) At the sublime sound of the Buddha (in his manifestation as a gandharva), Zen’ai becomes his disciple and attains arhathood (Senshū hyakuengyō, T 4, 200: 211a–212a). In this scripture, the Buddha is not just a spectator of a music performance; he himself becomes a musician and his music has the power to convert the king of the gandharva and cause him to attain arhathood. Here the power of music, far from being detrimental to Buddhist practice, enables one to attain liberation; the Buddha does not shun music, but appears as a virtuoso musician himself.

The Sutra of Druma, King of the Kiṃnara

But the most stunning scriptural endorsement of music can be found in another early scripture, the Sutra of the Questions by Druma, King of the Kiṃnaras, with its extended interaction between the Buddha Śākyamuni and the king of the kiṃnaras, Druma. And while a large portion of the sutra consists of standard teachings about prajñā-pāramitā doctrines, visualizations, and instructions on the characteristics of the bodhisattvas and their practices, it also presents an original view on music: At one point, the Buddha announces that king Druma is on his way to pay his respects to him, accompanied by multitudes of kiṃnaras, gandharvas, and other celestial beings. Immediately, King Druma begins to play his precious and beautifully decorated beryl koto (i.e., the vīnā), joined by all the heavenly musicians in his cortege. The sound pervades the universe and everything, from the cosmic Mount Sumeru to plants and trees, begins to sway as if inebriated. Almost all the members of the Buddha’s assembly, rise from their seats and, unable to control themselves, begin to dance. When asked, Mahākāśyapa and the other disciples can only say: “We can’t control ourselves! Because of the music of this koto, we cannot sit quietly and keep our bodies from dancing, and our minds can’t focus. . . . It’s something independent of our mind’s desire, we just can’t resist this rhythm. The music of the king of the Kiṃnaras . . . shakes my mind like trees in a storm and it can’t stand still” (pp. 370c–371a). This is in line with other scriptures, in which music is an obstacle to Buddhist practice. Here, however, the Buddha goes beyond that perspective and makes clear that because of his deep knowledge of skillful means, King Druma can use the intrinsic power of music for salvific purposes. The kiṃnaras—continues the Buddha—like the gandharvas and mahorāgas, love music; with their music, they arouse love for, belief in, and respect for the Dharma, which in turns generates the sounds of the three jewels, the sounds of the six pāramitās, and the sounds of all teachings. Because of his merit, in the future King Druma will become a Buddha ruling over his own Buddha-land.

Significantly, in this scripture the Buddha instructs the bodhisattva Tengan, his main interlocutor, to address his questions about music and its effects directly to King Druma—a powerful endorsement of the spiritual state of the latter. This is a summary of their dialogue:

Druma: “The musical voice of sentient beings originates from the body and from the mind.”

Tengan: “No, because the body, like plants and stones, is not intelligent, and the mind, being formless, has no vision or touch and doesn’t make speeches.”

Druma: “If it’s distinct from body and mind, where does it come from?”

Tengan: “Ideation creates music and sound. If there is no voice in empty space, then sound does not emerge.”

Druma: “All sounds emerge from empty space. Sound has the nature of emptiness: when you finish hearing it, it disappears; after it disappears, it abides in emptiness . . . all dharmas . . . are emptiness. All dharmas are like sound . . . Sound . . . has no origin and is not subject to extinction, therefore it is pure, immaculate, and incorruptible, like light and the mind.”

This sutra, in which King Druma argues that music is the very condition of realized emptiness and hence a manifestation of awakening, is a powerful endorsement of music as a proper Buddhist salvific activity. The sutra, however, only speaks about the celestial music of the kiṃnaras, not about human music, thus reiterating the standard understanding of other early Buddhist texts and preserving, with this gap, a fundamentally ambivalent stance. Exegesis in medieval Japan would bridge this gap and give an important role to a certain type of human music, the ceremonial music and dances of Gagaku and Bugaku.

Final Considerations: King Druma, Japanese Gagaku, and the Possibility of Buddhist Music Today

At a time in which most Buddhist scriptures saw music essentially as entertainment (either a way to deal with possible patrons or as a pleasant offering to the buddhas), or as the soundscape of pure lands, the Sutra of King Druma provided the first cogent Buddhist philosophy of music as closely related to the concept of emptiness, its practices (samādhi), and its results (prajñā-pāramitā). This sutra, far from being a doctrinal anomaly, became central for a number of developments in Japanese Buddhism and its attitudes toward the performing arts, especially the ceremonial music and dance known as Gagaku. (Japan is, together with Tibet, the only Buddhist culture that has created and sustained a long and rich tradition of Buddhist ritual music and dance.)

Now, Gagaku is mostly understood as deeply related to the imperial court and Shinto shrines, but historically, Gagaku (and its dance repertory, Bugaku), has been transmitted mostly at two Buddhist temples, Kōfukuji in Nara and Shitennōji in Osaka; a third center of transmission, the imperial court in Kyoto, had close connections with Iwashimizu Hachimangū, which prior to the Meiji era was another full-fledged Buddhist temple. Gagaku—as both instrumental music (kangen) and dance (Bugaku)—was widely used, along with Shōmyō chanting, in large-scale Buddhist rituals known as Bugaku hōyō (a rich tradition that continues today, primarily in the Shōryō-e ceremony for Prince Shōtoku at Shitennōji and at a few other temples). It is possible that the Sutra of King Druma provided a model for such ceremonies.

Japanese developments related to the Buddhist conceptions of music went beyond that and extended to at least three other areas. First, the performance of Gagaku and Bugaku came to be considered a salvific activity: since music was both a type of offering and an instantiation of the pure lands in this world, it would generate merit for the performers and the audience; this was known as “playing instrumental music as a karmic activity for rebirth in a pure land” (kangen mo ōjō no gō to nareri). Second, in line with Esoteric Buddhist teachings, music came to be seen as a fundamental aspect of the enlightened cosmos, deeply related to the nature of reality, as initially suggested by Kūkai and developed by Annen in his Shittanzō, a book on Sanskrit linguistics, which also contains important sections on music theory, and which became one of the bases for Shōmyō music theory. Finally, the scriptural separation between heavenly music and human music was practically abolished: since scriptures about music in the heavenly realms listed all instruments used in early Gagaku ensembles (for example, paintings of Amida coming to this world often include heavenly beings playing Gagaku instruments), human-made Gagaku was considered to be comparable in beauty and power to the heavenly music of the pure lands.

Based on scriptural sources and a long Japanese musical tradition, it may be possible today to further expand the Buddhist understanding of music and treat it (not only Gagaku, but any type of music) as something deeply related to our body-minds and our environment, very much in line with developments in contemporary music influenced by John Cage’s esthetics and the works of Pauline Oliveros, both directly influenced by Buddhism. As such, it should be possible to make music the subject of practices in which the practitioners focus on sounds as they resonate both within themselves and with the surrounding environment, as a way to attain a higher awareness of the interrelatedness of all things and to experience, somehow, the concept of emptiness, as King Druma explained in his sutra.

Fabio Rambelli is Distinguished Professor of Japanese Religions and Cultural History and International Shinto Foundation Chair in Shinto Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His publications include: Buddhist Materiality (2007), The Sea and the Sacred in Japan (2018), and Gagaku: The Cultural Impact of Japanese Ceremonial Music (2025). He is also a musician and plays the shō mouthorgan (both in Gagaku and in contemporary music). He has released three CDs of original music with various units.