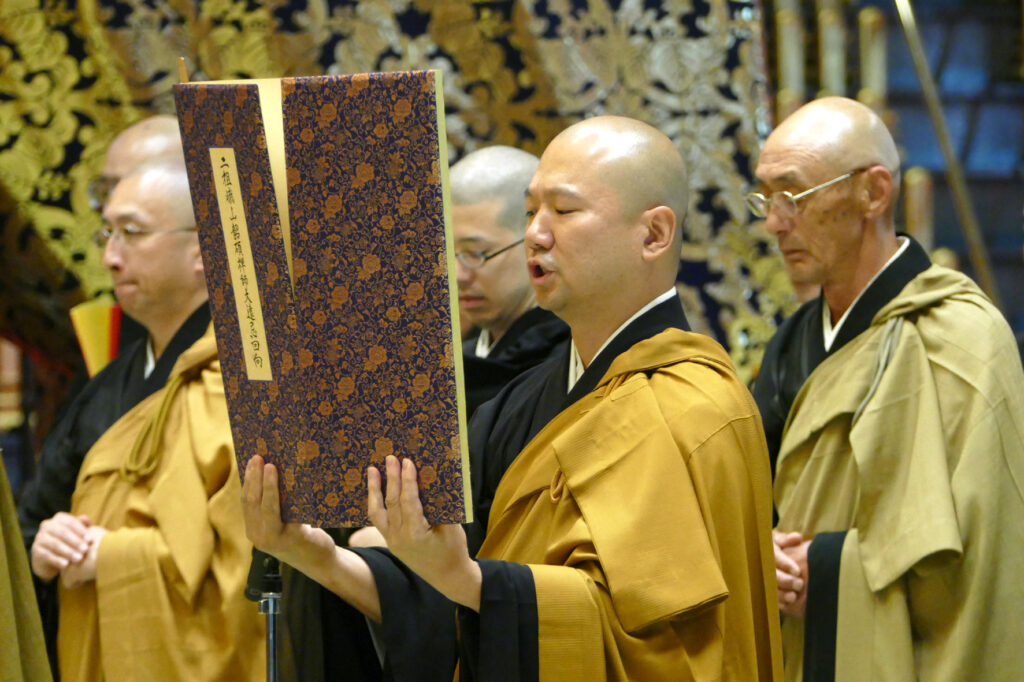

Ōyama Bunryū intones a transfer of merit during the 650th grand death anniversary commemoration of the Sōtō Zen master Gasan Jōseki at the head temple Sōjiji in Tsurumi, Yokohama, in 2015. Photo by the author.

Music is not only a means of expressing religious devotion; it also helps create a community of fellow practitioners who support each other in their religious pursuits.

Introduction

In all religions, music plays a vital role in communicating with the sacred. Priests sing hymns asking deities for protection; shamans play drums to communicate with spirits; devotees intone sacred words praying for a favorable rebirth of the deceased. Accordingly, music and sounds are central aspects of Japanese Buddhism, and temples are characterized by a rich soundscape, ranging from the singing of highly melismatic pieces in free rhythm, to the more syllabic recitation of sutras on a single pitch in a fixed rhythm, to the sound of musical instruments that reverberate through the temple compound and guide monastics through their daily schedule.

Buddhist music is mostly vocal music, and both clerics and lay devotees intone sacred texts. Clerics usually sing more complex chants during elaborate ceremonies, such as the Buddha’s memorial service, the Lotus Repentance Ceremony, or the rolling reading of the Great Sutra on the Perfection of Wisdom.1 The most elaborate form of Japanese Buddhist chant sung by clerics is shōmyō, literally meaning “bright voice.” Within the category of shōmyō, we find various styles that can be distinguished by their level of melodic movement. For some texts, it is necessary that listeners understand the content, and therefore reciters use few melodic embellishments. For other texts, the sound is more important, and practitioners employ many melisma; in these cases, music is often seen as an offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas or as a means to sonically express cosmic truth. Only occasionally musical instruments, such as small bells, sounding bowls, gongs, and cymbals, are used to signal the beginning or end of ritual sequences. All schools developed their distinctive repertoire of shōmyō with a unique style and repertoire that has been handed down over the centuries and is still performed today.

Brief History of Japanese Buddhist Music

Buddhist chant was introduced to Japan together with Buddhist doctrine and practices, first from Korea and later from China. Already in the eighth century, the major Buddhist temples in Nara had their own music departments. One of the earliest extant references to Buddhist music describes the eye-opening ceremony of the Mahāvairocana Buddha at Tōdaiji in Nara in 752 and states that more than one thousand monks sang the standard liturgical pieces Praise of the Buddha (Nyoraibai), Scattering Flowers (Sange), Sanskrit Sound (Bonnon), and Priest Staff (Shakujō)—four pieces that are still vocalized today during major ceremonies. Around that time instrumental gagaku music, including pieces for dance, was also introduced to Japan and integrated into elaborate rituals. The combination of gagaku with shōmyō created impressive ceremonies with a beautiful soundscape, which served as an offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas.

With the founding of the Shingon and Tendai schools in the Heian period (794–1185), many new liturgical pieces were introduced from China to Japan: Kūkai (774–835), the founder of the Shingon school, introduced the core repertoire of Shingon shōmyō, while Ennin (794–864), a disciple of the Tendai school founder Saichō (767–822), transmitted many important shōmyō pieces from China and laid the foundation of Tendai shōmyō. Monks in these two traditions emphasized the importance of the vocalization of sacred texts as a means of achieving soteriological aims and realizing buddhahood in this very body. Consequently, learning to sing sacred texts became a vital aspect of the monastic curriculum in these two schools.

In order to transmit and preserve the melodies of liturgical pieces, monks developed various musical notation systems. The oldest extant examples of Buddhist music notation in Japan date from the tenth century. But most remarkably, the oldest printed music notation in the world is a shōmyō notation produced at Kōyasan in 1472, one year before the first European printed music notation, attesting to the importance of music in Japanese Buddhism.

The tenth century saw important innovations in the development of the Japanization of Buddhist liturgy. During the first centuries after the introduction of Buddhism to Japan, clerics vocalized texts in Chinese or Sanskrit, and thus Japanese devotees were not able to understand the content of the chants. In the tenth century, Japanese clerics therefore invented new liturgical forms that were vocalized in Japanese, such as offertory declarations (saimon), Japanese hymns (wasan), and Buddhist ceremonials (kōshiki).

The new Kamakura schools that emerged in the thirteenth century developed their unique musical traditions, but most of them were influenced by Tendai shōmyō because the founders of these new schools had originally been Tendai monks. In the seventeenth century, new styles of Buddhist chant were again introduced from China when Yinyuan Longqi (Jpn., Ingen Ryūki, 1592–1673) came to Japan and founded the Ōbaku school of Zen.

Japanese Buddhist music underwent another innovative wave during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when Western musical styles were brought to Japan. Some Buddhist reformers enthusiastically embraced the newly introduced Western musical styles and composed Buddhist songs using those styles. Inspired by the renewed interest in composing novel Buddhist music, some clerics turned to traditional Japanese genres and adopted them to the new times. They, for example, turned to Buddhist pilgrim songs to create new lineages of hymn chanting in groups, which could serve to instruct the laity in Buddhist concepts and practices.

In this way, Japanese Buddhist chant has evolved over the centuries. While traditional chants created centuries ago continue to be handed down and form the central part of Buddhist liturgy, new styles have been added to the repertoire. Still today, young monks and nuns dedicatedly learn the traditional chants of their schools. Some of them also engage in innovative projects, such as Buddhist pop music, rap, and voice meditation. Thus, traditional and contemporary forms coexist in an ever-evolving practice.

Kōshiki and the Commemoration of the Buddha’s Death

One vital ritual genre that features shōmyō is kōshiki (Buddhist ceremonials). This ritual genre was developed in the late tenth century in the context of Tendai Pure Land belief and spread throughout all Buddhist schools in the following centuries. Works in this genre have been composed and performed for various objects of veneration, such as buddhas, bodhisattvas, eminent monks, sutras, and kami. The central text recited during these rituals explains the virtues of the object of worship and Buddhist concepts in an easily understandable manner. Therefore, kōshiki became very popular and strongly contributed to the spread of Buddhism to all social strata.

Over the centuries around 400 works in this genre were composed, but the highpoint of composition was in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. One of the most prolific authors was the Kegon-Shingon monk Myōe (1173–1232), who is today well known for his dream diary, in which he recorded the visions that guided his practice. Myōe’s Shiza kōshiki (Kōshiki in four sessions), composed for the Buddha’s memorial day in 1215, is considered a masterpiece in the genre. Myōe’s Shiza kōshiki is actually not one kōshiki but a set of four kōshiki to be performed in sequence: a kōshiki on the Buddha’s passing, one on the Sixteen Arhats, one on the remaining traces of the Buddha’s activities, and one on the Buddha’s relics. The central texts of these four works describe in an emotionally evocative and dramatic manner the passing of the Buddha and his heritage. Myōe himself was strongly devoted to Śākyamuni Buddha and lamented having been born well after the Buddha’s death. He had long planned to visit India, the land of the Buddha, but was never able to fulfill this aspiration. His Shiza kōshiki, as well as other rituals and dreams, seems to have served as a means of visualizing this journey without actually undertaking it.

When Myōe performed his Shiza kōshiki during the Buddha’s memorial service, the ritual took over twenty hours. It started around 11 am on the fourteenth day of the second lunar month and ended around 8 am on the next day. The ritual was performed throughout the night and there was no time for sleep. People from all social strata gathered in communion to commemorate the Buddha.

The main part of the ritual was the recitation of the central text of the kōshiki. Usually, the recitation of this liturgical text takes at least one hour. In order to keep the attention of the audience, reciters need to add variation to their musical performance. This led to the development of a special recitation method that utilizes melodic formulas on three different pitch levels: a low (first) pitch level; a middle (second) pitch level whose central pitch is either a fourth or fifth above the central pitch of the low pitch level; and high (third) pitch level, which is one octave above the low pitch level. A change of pitch level highlights important passages; the highest pitch level marks a high point and is sparingly used.

We do not know how Myōe recited his kōshiki. In the early stages of kōshiki, the officiant had a lot of freedom for improvisation and was able to determine the distribution of the pitch levels himself. In the Kamakura period, clerics started to add musical notation to the texts, and the musical realization of a kōshiki became fixed. Manuals from the Tokugawa period show how later reciters used the three pitch levels to convey the emotions of the text. For example, in the following excerpt from the kōshiki on the Buddha’s death, the reciter uses the highest pitch level to express the deep sorrow over this loss:

[First pitch level]

The Tathāgata further addressed the great assembly and said:

“Now, my body is racked with pain.

The time of [final] nirvana has come.”

After speaking thus,

he entered various states of samādhi

in an order of his choosing.

After he arose from samādhi,

he expounded the marvelous dharma

for the assembly and said:

[Second pitch level]

“The fundamental nature of ignorance

has always been that of liberation.

I now abide in peace,

eternally in the radiance of quiescence.

This is called the mahā-parinirvāṇa.”

After he spoke to the assembly,

he leaned his whole body over and lay on his right side;

his head to the north, his feet to the south,

facing the west with his back to the east.

[Intermediate pattern]

Then he entered the fourth stage of samādhi

and achieved the mahā-parinirvāṇa.

[Third pitch level]

He closed his lotus blue eyes

and his smile of compassion disappeared forever.

His lips, red as the fruit of the bimbā tree, were sealed

and finally his pure, compassionate voice went silent.

In this way, the highest pitch level enhances the emotive effect of the narration about the Buddha’s passing, adding an emotional component to the text. The deep lament about the death of Śākyamuni Buddha, described in other passages of the kōshiki, is amplified by the high pitch of the male voice.

A distinctive feature of Myōe’s performance of the Shiza kōshiki was the participation of the laity. At the beginning of the ritual, lay devotees and clerics vocalized together the phrase “We take refuge in the purple-golden wondrous body that finally entered nirvana in the Śāla Grove of Kuśinagara,” and so the ritual started with communal obeisance. After the recitation of each of the central texts of the four kōshiki, laypeople and clerics continuously chanted “We take refuge in Śākyamuni Buddha” (namu shakamuni butsu) until the beginning of the next kōshiki. This collective chanting lasted for at least one hour. The vocalization of the Buddha’s name made the Buddha present. At the same time, the communal chanting transformed the individual participants into a group whose members formed karmic bonds with each other and the Buddha.

During Myōe’s lifetime, the Shiza kōshiki was relatively simple, and only a few other liturgical texts—including the aforementioned Praise of the Buddha, Scattering Flowers, Sanskrit Sound, and Priest Staff—were performed in addition to the central kōshiki text. For this reason, it was easy for Myōe and his fellow monks to integrate lay devotees. But after Myōe’s death and the adoption of this ritual by the Shingon clerics, the ritual form became increasingly complex and many difficult-to-sing shōmyō pieces were added. Because laypeople did not have the necessary training in shōmyō, lay participation gradually diminished. When clerics on Kōyasan perform the Shiza kōshiki during the Buddha’s memorial service today, laypeople do not join the vocalization. But the rich soundscape with its diverse shōmyō pieces takes the attendees on a musical journey to remember the Buddha and his life.2

Goeika and the Modernization of Buddhist Liturgy in the Twentieth Century

In medieval Japan, Buddhists also created songs that were sung outside of ritual contexts by the laity and clergy. One such genre was goeika (devotional songs in the form of waka poems), which pilgrims intoned when visiting sacred sites. Singing goeika was an individual practice, and practitioners had a lot of freedom in how to intone the songs.

In the early twentieth century, reformers turned to goeika and created lineages in which a standardized performance practice of goeika was taught to lay devotees. The first lineage, the Yamatoryū, was founded in 1921 by the layman Yamasaki Chikumatsu (1885–1926) after he had found relief from a severe skin disease through his Buddhist faith. Reformers of the Japanese Buddhist schools soon followed his example and created sectarian lineages of goeika chanting. As the devotional songs sounded similar to popular music played on the radio at that time, goeika quickly gained popularity among lay devotees. The leaders of the newly founded goeika lineages promoted the singing of hymns as a vital Buddhist practice. For example, Sogabe Shunnō (1873–1959), who is considered the founder of Kōyasan’s goeika lineage, interpreted goeika as shōmyō for lay people.3

During World War II, the goeika lineages stopped their activities. After the end of the war, all schools restarted their outreach, and some schools that had not founded goeika lineages before the war started one for the first time. This included the Sōtō Zen school, which established the Baikaryū (Plum Blossom Style) as their goeika lineage in the early 1950s. Niwa Butsuan (1880–1955), who inspired its founding, saw this as an opportunity to revive the school and heal the hearts of people after the long and devastating war.4

The lineages created groups in which the particular style of that lineage is taught. While intoning the pentatonic melodies, the singers indicate the rhythm with two bells: with the right hand they play a shō bell, and with the left they sound a rei bell, which is basically a vajra bell. Vajra bells are usually played by clerics in esoteric rituals. Using this kind of bell in goeika practice provided laypeople the opportunity to handle precious ritual implements that originated in esoteric Buddhism. The teachers of the groups not only instruct practitioners on how to sing the melodies but also teach devotees Buddhist values and ideas when they explain the lyrics. Thus, the goeika groups are a vital means for outreach and religious edification.

In some schools, the invention of a sectarian goeika lineage also led to changes in the liturgy. The Sōtō school headquarters, for example, created suggestions for temples on how they could integrate the newly created Baikaryū groups into rituals. As a consequence, temples that have a Baikaryū group started to ask the members to sing during various services, such as the feeding of hungry ghosts during o-bon. On these occasions, the groups usually sing the Japanese Hymn for the Three Treasures when the clerics enter the hall, and when the priests leave the hall, they sing a solemn song in minor mode expressing veneration of the object of worship. Often the groups sing another hymn when the officiant provides offerings on the altar. Goeika sounds significantly different from traditional shōmyō and sutra chanting. By integrating goeika into rituals, clerics created ceremonies with a fresh soundscape and thus modernized traditional liturgical forms.

The participation of laypeople singing goeika in traditional rituals reminds one of Myōe’s Shiza kōshiki, during which laypeople sang the Buddha’s name. Music is not only a means of expressing religious devotion; it also helps create a community of fellow practitioners who support each other in their religious pursuits. During the ritual, they harmonize with each other while chanting in unison, and they can feel the reverberation of multiple voices in their bodies. This experience helps forge deeper connections among participants and, most importantly, creates karmic bonds to the buddhas and bodhisattvas to whom they pay homage.

Notes

- For a performance of the rolling reading of the Great Sutra on the Perfection of Wisdom, see, for example, https://www.youtube

.com/watch?v=k03yqLhsGg4. For a performance of Sōtō Zen shōmyō, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v

=ato8vvNjK3I. - This section is based on my research published in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. (Mross, Michaela [2016]. “Vocalizing the Lament over the Buddha’s Passing: A Study of Myōe’s Shiza kōshiki.” In Kōshiki in Japanese Buddhism. Special Issue of the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 43/1: 89–130.) I would like to express my gratitude to the editors for allowing me to republish this material.

- Sogabe, Shunnō (1930). “Kyōdō no kokoroe.” In Kōyasan daishi kyōkai Kongōkō Goeika wasan shōkai, 5th edition (Kōyasan: Kōyasan Daishi Kyōkai Kongōkō Sōhonbu).

- Niwa Renpō (1980). Baika kai: Waga hanshō (Shizuoka: Tōkeiin), p. 156. Various audio recordings of Baikaryū hymns are available online; see, for example, Ono Takuya’s blog (https://tgiw.info/weblog/otonae) or the YouTube channel of Baikaryū teachers in Akita Prefecture (https://www.youtube.com/@梅友チャンネル).

Michaela Mross is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Stanford University, specializing in Japanese Buddhism. Drawing on extensive fieldwork in Japan, she has published numerous articles on rituals and sacred music. Her recent book, Memory, Music, Manuscripts, examines the history of kōshiki in Sōtō Zen from the 13th century until today. She is currently working on a monograph on goeika, which will showcase the vital role music has played in the modernization of Japanese Buddhism over the past seventy years.